Sustainable Forestry and the Ancient Timbers of Kiso, Japan

The world’s oldest remaining wooden structures are the 32-meter high, five story pagoda, and Kondo, or Sanctuary Hall, of Japan’s Horyu-ji Temple, dating back over 1,300 years and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

For thousands of years the Japanese have been building things from wood. Large structures such as houses, shrines, temples, bridges, ships, castles, even smaller daily life items, such barrels for the fermenting of sake and other foods, tansu chests, tables, even drinking vessels were made from wood. Japanese carpenters and craftsmen mastered their trade, producing some of the finest woodworking techniques in history. It was not just their skill nor their tools that helped them to achieve this recognition, but the wood they worked with.

One of the finest of timbers used is Hinoki, the Japanese cypress, a high-quality rot-resistant ornamental timber with a faint, aromatic scent and a rich, straight grain, said to become stronger and more durable over time. The scent is believed to repel insects, helping to preserve the wood. Hinoki trees grow slowly but are usually straight and reach average heights of 35 meters, with trunks over one meter in diameter. Some of the even bigger trees are treated as sacred.

Of the different types of Hinoki, Kiso Hinoki, grown in the rich, fertile, high rainfall and harsh cold conditions of southern Gifu Prefecture’s mountainous regions has been recognized from ancient times as the finest and most valuable of timbers.

The 1,300 year-old World Heritage Horyu-ji Temple’s ancient structures were made from Kiso Hinoki. The pagoda’s central pillar of Kiso Hinoki was scientifically dated to have been felled in the year 594, and is most probably one of the reasons why it has survived to this day. Every 20 years from time immemorial, Japan’s most sacred Ise Jingu Shrine has been rebuilt afresh using only Kiso Hinoki. The old shrine wood is then passed on to other shrines across Japan and re-used in the Shinto rebuilding tradition of renewal.

During Japan’s feudal Edo period (1603-1868) the Kiso region came under the control of the Owari Tokugawa clan, the politically and financially strongest of the three branches of the ruling Tokugawa clan. The Shogun himself, Tokugawa Ieyasu, demanded that the Owari Tokugawa have the grandest castle of all, and so their base castle and palaces at Nagoya was built with the biggest, finest of Kiso Hinoki, cut in the Kiso mountains and floated down the rivers to Nagoya.

The lords of Nagoya realized the importance of the timber, and that maintaining the resource was vital for the future. They formed one of the world’s earliest sustainable forestry care systems for the great trees’ protection and regrowth, and even appointed teams of Yamamori, forestry managers, to care of the valuable resources, which, like the Horyu-ji Temple, built from quality Kiso Hinoki, remain to this day.

INTERVIEW

The Yamamori Museum is your home, right?

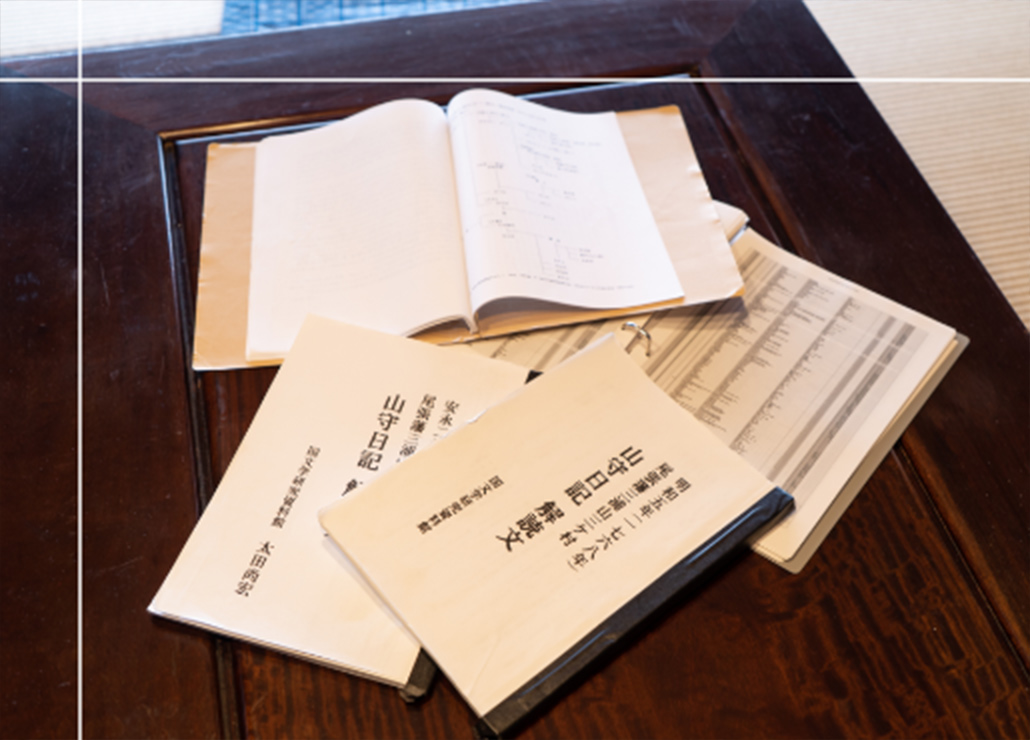

Yes, that’s right. My ancestors were appointed as Yamamori around 1730 and managed the mountains until the end of the Edo period (1868). There are still many ancient documents remaining relating to the Yamamori'slife and work at that time. Currently, with the cooperation of the Tokugawa Reimeikai Research Institute and prefectural researchers, we are collating,preserving and deciphering the materials, while maintaining and operating our home as a private museum.

What does a Yamamori do?

The Yamamori’s job is to manage the mountains and forests. The work involves various tasks, including forest management, conservation, care and creation. My ancestors served as Yamamori for six generations. It was a hereditary system in which they started as apprentices, and succeeded their fathers when they died. The Yamamori diaries kept in this museum document not just the work of the Yamamori, but also the lives of the people at the time. Reading the old records left by my ancestors, I discovered ancient forestry methods that I want to pass on to the future.

We’ve heard that the future of Kiso Hinoki is in danger.

Gifu Prefecture’s Nakatsugawa City area has always had abundant forest resources. During the Edo period (1603-1868) there was a mountain where hawks were bred called Suyama that was made off limits to all, and so there was a lot of good wood growth there. Then from around 1600, many castles were built, and apparently 70% of the high-quality cypress was cut down to build them, and so the trees disappeared from the mountain. Especially the older, bigger trees, a few hundred years old, were all cut down in the 100 years between 1600 and 1700, leaving only younger, thinner trees. Then, over the next 2 to 300 years, my ancestors, the Yamamori, returned the forests to their original state. So the hardships and the efforts of the Yamamori are in a way, connected to the present.

How did you protect and regenerate the mountain?

Efforts to gradually restore the mountain to its original condition began around 1700. Our ancestors felt it was their mission to preserve this valuable forest resource for our descendants. Incidentally, the forestry styles of the past are a little different than modern day tree planting. Basically, it was all left to nature to regenerate. Since there was no high-tech machinery, we used the power of nature to regrow the forest slowly. I think this is something to consider for the future of Japan’s forestry.

What are your goals for the future as a descendant of the "Yamamori"?

There is a desire within the community to preserve Kiso Hinoki, however there are many challenges and issues such as a shortage of successors. Mountain reforestation done by humans needs to be carefully maintained over a long period of time. If not cared for properly, the mountains will be in disarray. I believe the time has come to learn the best points from the old techniques and create a new form of mountain forestry.

I personally believe my mission is to create a database from the enormous amount of records kept by my Yamamori ancestors, and pass them on to the next generation. If we don’t preserve the records now, nothing will be left. I hope to gain some hints of where to start from those documents. It is important to keep records of the mountain’s regeneration, and take action to match each stage.

Interview with;

Yamamori Shiryokan Museum Director, Mr. Tetsuro Naiki.

For 140 years, from 1730 to 1868, six generations of Mr.Naiki’s ancestors served as the ruling Owari feudal clan’s Miurayama Mikamura Yamamori.

His 260-year-old home, built in 1756, holds tens of thousands of Yamamori documents.

Yamamori Shiryokan Museum

Reservations required for facility tours.

Inquiries are required in advance.

Contact: Central Japan Tourism Association

TEL: 052-602-6651