The Women of the Sea, Japan’s Traditional Ama-San Divers

Ama, it means “Woman of the Sea”, and even in technical, industrial, modern-day Japan, the few remaining traditional Ama, women divers, adhere to long held historical beliefs and practices said to stretch back over 2,000 years, and as such, they are venerated with near legendary status.

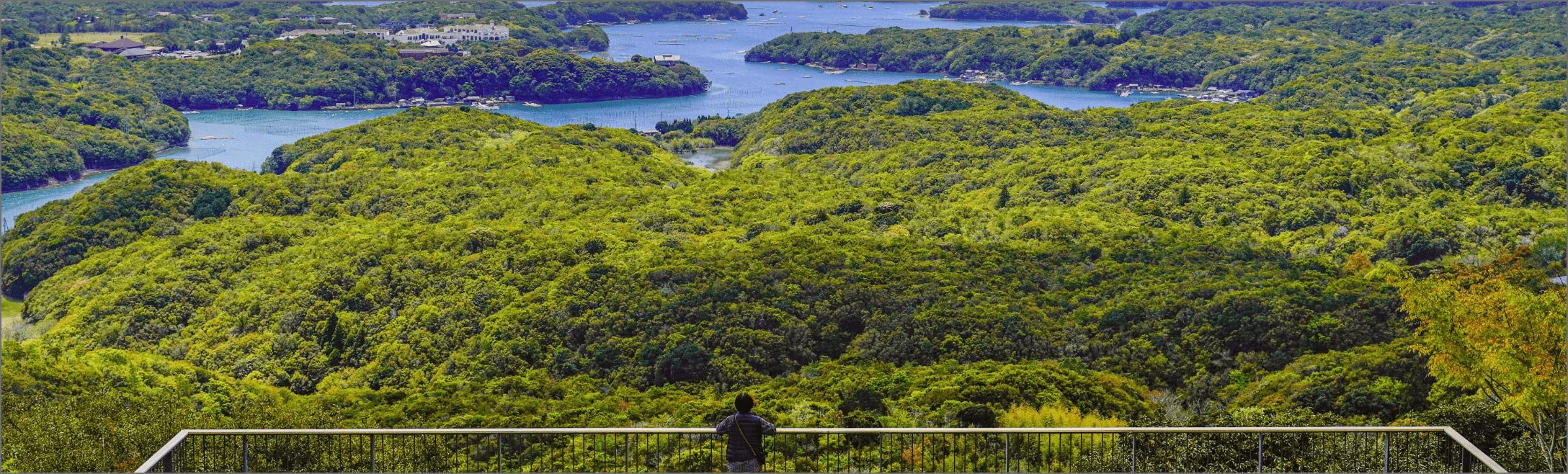

The ancient techniques and the numbers of traditional Ama women divers are slowly disappearing as times change. Demand for their activities and numbers of young women willing to undergo the training and maintain the traditions continues to diminish. However, the disciplines are continued in Mie Prefecture where the largest number of traditional Ama left in Japan, around 100 women, remain active in Osatsu-cho.

As recently as the 1960’s, the women Ama divers wore only a white loincloth. As the art became more popular with tourists, and social norms changed, so too did the women diver’s outfits, into full body white cloth swimwear, and more recently yet again, into a modern-day wet suit. The only traditional article of clothing still being used is the headscarf, adorned with special symbols, believed to bring fortune to the women divers, while warding off bad luck.

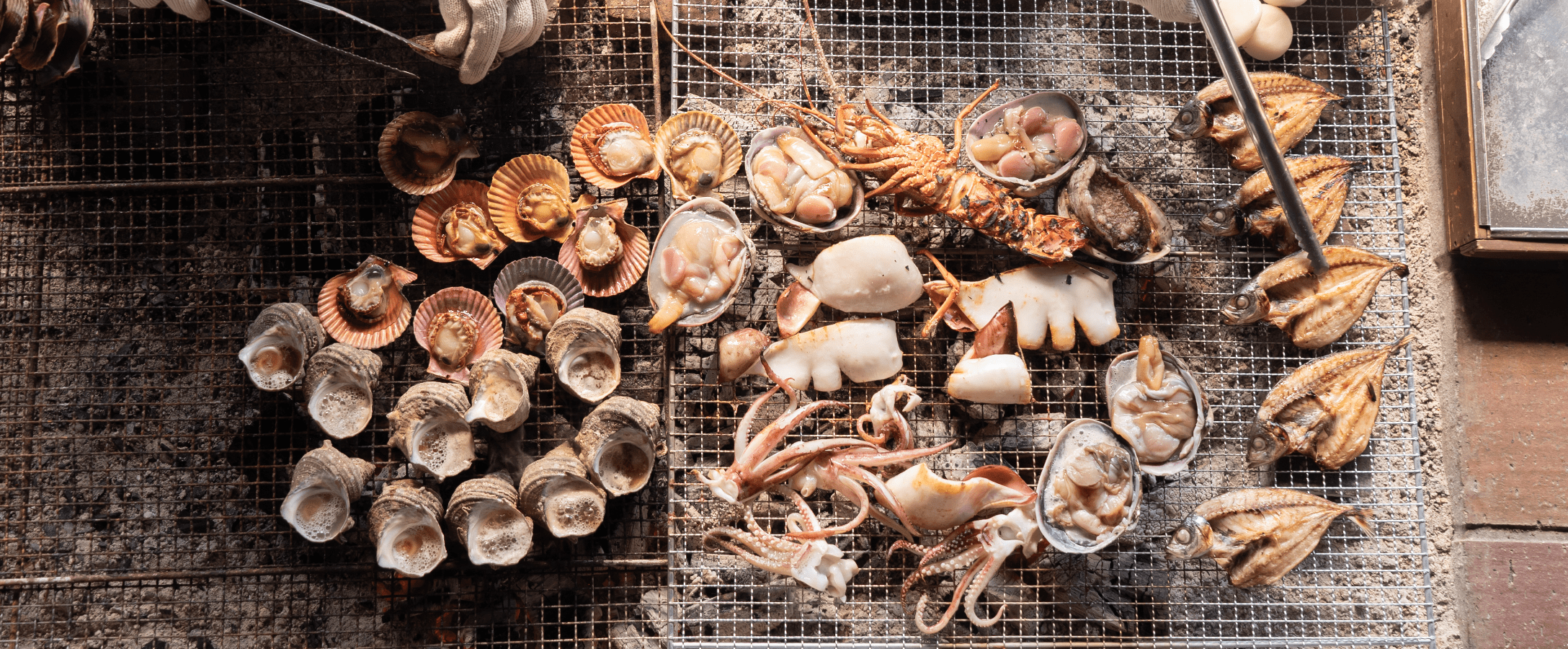

Without snorkels or diving equipment the women free-dive to depths of around 4 meters in search of seasonal delicacies including shellfish such as abalone, turban shells, and sea urchins, various seaweeds including wakame and hijiki, sea cucumber and even lobster.

Most of the women commenced their training from as early as 12 years of age, and remain underwater for around 50 seconds. Among the many unique skills of the Ama-san is the special breathing technique known as Isobue, a sharp whistle sound they make to steady their breathing before and after diving that also serves to let the other Ama-san know where they are, and that they are safe. Ama divers often work as a small group, traveling daily to open waters by boat and diving for a short, set time, usually around 90 minutes or so, during which they collect as much seafood as they can.

Today, the Ama traditions continue, although the numbers are few. Many Ama-san now ply their trade for the tourist industry, taking visitors on the boats to watch the women diving and bringing their catch to the surface. Another popular attraction is being allowing into the special seaside Amagoya huts, where the Ama-san cook their freshly caught daily takings on roaring fires, and entertain the visitors with stories about the life, history and culture of the Ama, women of the sea.

INTERVIEW

What do you consider enjoyable, rewarding or attractive about being an Ama-san diver?

Ama is a life-threatening job. Nature is our partner, and so we’re side by side with danger. Those with many years of experience have faced frightening situations many times over. Even then, when I experience a good catch, I look forward to doing my best again next dive. One of the great attractions and rewards of this job is knowing that you can profit off your efforts, and that as you age, your techniques improve. Sometimes you have a certain feeling that this spot will be rewarding, and you do catch a lot. In some cases, this skill peaks around 70 years old. It’s not something you can learn from someone else, or just through practicing, experience is most important. There is no retirement age for Ama, so I hope to continue until I’m ready to retire. Incidentally, the youngest active Ama-san is currently 38 years old.

What is the life of an Ama-san like?

On the days when I go fishing, I work as an Ama, and on other days I work in the rice paddies and fields. All the Ama are hard workers.

What are the unique customs of the Ama-san Diver?

On December 28, the last day of work, three stones are lined up with small offerings of shrimp dishes and servings of shredded carrot and daikon radish. This is to thank the sea for an accident-free year. At dawn on New Year’s Day, we return with an offering of sliced fish and other side dishes to pray for a safe year ahead. This is a local custom that has been handed down from generation to generation.

What makes you proud to be an Ama-san?

I grew up watching my parents who were Ama divers. When I was little, I would imitate the Ama-san. Since I was little, the sea has played a major role in my life, so I’m proud to work in that sea. When you dive into the ocean, at first you don’t know where the catch will be, but I watched the older Ama-san, and through experience, finally became a fully-fledged Ama. From parents to children, from seniors to juniors, the senses and techniques that have been passed down are also our treasures.

What is the future of traditional Ama-san fishing?

When our generation (late 60's to early 70's) got married, the mother-in-law was an Ama-san, and the bride was also an Ama. There were two Ama in the one household. These days there is usually only one Ama per house. There used to be 500 to 600 Ama in this area, but now we number less than 100. It’s a pity, but I think it’s a sign of the times. In the last ten years or so, the catch has decreased dramatically due to global warming, so I think the situation will become more difficult in the future.

Interview with;

Head Ama, Mrs. Nakamura.

Ama, Mrs. Nakayama

Amagoya hut, Ozegosan

Osatsu Gyoko, Osatsu-cho, Toba City, Mie Prefecture, 517-0032.

TEL: 0599-33-7453 (Osatsu Ama Culture Museum) *Japanese Only

For On Line reservations:

https://osatsu.org/en/html/form.php

(reception until 17:00 the day before)